There is a longer discussion about this that has been going on in the US, continental European, and many other parts of the academic/policy/legal/media complexes and their intersection. Useful points of reference are Magna Charta Universitatum (1988), in part developed to stimulate ‘transition’ of Central/Eastern European universities away from communism, and European University Association’s Autonomy Scorecard, which represents an interesting case study for thinking through tensions between publicly (state) funded higher education and principles of freedom and autonomy (Terhi Nokkala and I have analyzed it here). Discussions in the UK, however, predictably (though hardly always justifiably) transpose most of the elements, political/ideological categories, and dynamics from the US; in this sense, I thought an article I wrote a few years back – mostly about theorising complex objects and their transformation, but with extensive analysis of 2 (and a half) case studies of ‘controversies’ involving academics’ use of social media – could offer a good reference point. The article is available (Open Access!) here; the subheadings that engage with social media in particular are pasted below. If citing, please refer to the following:

Bacevic, J. (2018). With or without U? Assemblage theory and (de)territorialising the university, Globalisation, Societies and Education, 17:1, 78-91, DOI: 10.1080/14767724.2018.1498323

——————————————————————————————————–

Boundary disputes: intellectuals and social media

In an analogy for a Cartesian philosophy of mind, Gilbert Ryle famously described a hypothetical visitor to Oxford (Ryle 1949). This astonished visitor, Ryle argued, would go around asking whether the University was in the Bodleian library? The Sheldonian Theatre? The colleges? and so forth, all the while failing to understand that the University was not in any of these buildings per se. Rather, it was all of these combined, but also the visible and invisible threads between them: people, relations, books, ideas, feelings, grass; colleges and Formal Halls; sub fusc and port. It also makes sense to acknowledge that these components can also be parts of other assemblages: for instance, someone can equally be an Oxford student and a member of the Communist Party, for instance. ‘The University’ assembles these and agentifies them in specific contexts, but they exist beyond those contexts: port is produced and shipped before it becomes College port served at a Formal Hall. And while it is possible to conceive of boundary disputes revolving around port, more often they involve people.

The cases analysed below involve ‘boundary disputes’ that applied to intellectuals using social media. In both cases, the intellectuals were employed at universities; and, in both, their employment ceased because of their activity online. While in the press these disputes were usually framed around issues of academic freedom, they can rather be seen as instances of reterritorialization: redrawing of the boundaries of the university, and reassertion of its agency, in relation to digital technologies. This challenges the assumption that digital technologies serve uniquely to deterritorialise, or ‘unbundle’, the university as traditionally conceived.

The public engagement of those who authoritatively produce knowledge – in sociological theory traditionally referred to as ‘intellectuals’ – has an interesting history (e.g. Small 2002). It was only in the second half of the twentieth century that intellectuals became en masse employed by universities: with the massification of higher education and the rise of the ‘campus university’, in particular in the US, came what some saw as the ‘decline’ of the traditional, bohemian ‘public intellectual’ reflected in Mannheim’s (1936) concept of ‘free-floating’ intelligentsia. Russell Jacoby’s The Last Intellectuals (1987) argues that this process of ‘universitisation’ has led to the disappearance of the intellectual ferment that once characterised the American public sphere. With tenure, he claimed, came the loss of critical edge; intellectuals became tame and complacent, too used to the comfort of a regular salary and an office job. Today, however, the source of the decline is no longer the employment of intellectuals at universities, but its absence: precarity, that is, the insecurity and impermanence of employment, are seen as the major threat not only to public intellectualism, but to universities – or at least the notion of knowledge as public good – as a whole.

This suggests that there has been a shift in the coding of the relationship between intellectuals, critique and universities. In the first part of the twentieth century, the function of social critique was predominantly framed as independent of universities; in this sense, ‘public intellectuals’ were if not more than equally likely to be writers, journalists, and other men (since they were predominantly men) of ‘independent means’ than academic workers. This changed in the second half of the twentieth century, with both the massification of higher education and diversification of the social strata intellectuals were likely to come from. The desirability of university employment increased with the decreasing availability of permanent positions. In part because of this, precarity was framed as one of the main elements of the neoliberal transformation of higher education and research: insecurity of employment, in this sense, became the ‘new normal’ for people entering the academic profession in the twenty-first century.

Some elements of precarity can be directly correlated with processes of ‘unbundling’ (see Gehrke and Kezar 2015; Macfarlane 2011). In the UK, for instance, certain universities rely on platforms such as Teach Higher to provide the service of employing teaching staff, who deliver an increasing portion of courses. In this case, teaching associates and lecturers are no longer employees of the university; they are employed by the platform. Yet even when this is not the case, we can talk about processes of deterritorializing, in the sense in which the practice is part of the broader weakening of the link between teaching staff and the university (cf. Hall 2016). It is not only the security of employment that is changed in the process; universities, in this case, also own the products of teaching as practice, for instance, course materials, so that when staff depart, they can continue to use this material for teaching with someone else in charge of ‘delivery’.

A similar process is observable when it comes to ownership of the products of research. In the context of periodic research assessment and competitive funding, some universities have resorted to ‘buying’, that is, offering highly competitive packages to staff with a high volume of publications, in order to boost their REF scores. The UK research councils and particularly the Stern Review (2016) include measures explicitly aimed to counter this practice, but these, in turn, harm early career researchers who fear that institutional ‘ownership’ of their research output would create a problem for their employability in other institutions. What we can observe, then, is a disassembling of knowledge production, where the relationship between universities, academics, and the products of their labour – whether teaching or research – is increasingly weakened, challenged, and reconstructed.

Possibly the most tenuous link, however, applies to neither teaching nor research, but to what is referred to as universities’ ‘Third mission’: public engagement (e.g. Bacevic 2017). While academics have to some degree always been engaged with the public – most visibly those who have earned the label of ‘public intellectual’ – the beginning of the twenty-first century has, among other things, seen a rise in the demand for the formalisation of universities’ contribution to society. In the UK, this contribution is measured as ‘impact’, which includes any application of academic knowledge outside of the academia. While appearances in the media constitute only one of the possible ‘pathways to impact’, they have remained a relatively frequent form of engaging with the public. They offer the opportunity for universities to promote and strengthen their ‘brand’, but they also help academics gain reputation and recognition. In this sense, they can be seen as a form of extension; they position the universities in the public arena, and forge links with communities outside of its ‘traditional’ boundaries. Yet, this form of engagement can also provoke rather bitter boundary disputes when things go wrong.

In the recent years, the case of Steven Salaita, professor of Native American studies and American literature became one of the most widely publicised disputes between academics and universities. In 2013, Salaita was offered a tenured position at the University of Illinois. However, in 2014 the Board of Trustees withdrew the offer, citing Salaita’s ‘incendiary’ posts on Twitter (Dorf 2014; Flaherty 2015). At the time, Israel was conducting one of its campaigns of daily shelling in the Gaza Strip. Salaita tweeted: ‘Zionists, take responsibility: if your dream of an ethnocratic Israel is worth the murder of children, just fucking own it already. #Gaza’ (Steven Salaita on Twitter, 19 July 2014). Salaita’s appointment was made public and was awaiting formal approval by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois, usually a matter of pure technicality once it had been recommended by academic committees. Yet, in August Salaita was informed by the Chancellor that the University was withdrawing the offer.

Scandal erupted in the media shortly afterwards. It turned out that several of university’s wealthy donors, as well as a few students, had contacted members of the Board demanding that Salaita’s offer be revoked. The Chancellor justified her decision by saying that the objection to Salaita’s tweets concerned standards of ‘civility’, not the political opinion they expressed, but the discussions inevitably revolved around questions of identity, campus politics, and the degree to which they can be kept separate. This was exacerbated by a split within the American Association of University Professors, which is the closest the professoriate in the US has to a union: while the AAUP issued a statement of support to Salaita as soon as the news broke, Cary Nelson, the association’s former president and a prolific writer on issues of university autonomy and academic freedom, defended the Board’s decision. The reason? The protections awarded by the principle of academic freedom, Nelson claimed, extends only to tenured professors.

Very few people agreed with Nelson’s definition: eventually, the courts upheld Salaita’s case that the University of Illinois Board’s decision constituted breach of contract. He was awarded a hefty settlement (ten times the annual salary he would be earning at Illinois), but was not reinstated. This points to serious limitations of the using ‘academic freedom’ as an analytical concept. While university autonomy and academic freedom are principles invoked by academics in order to protect their activity, their application in academic and legal practice is, at best, open to interpretation. A detailed report by Karran and Malinson (2017), for instance, shows that both the understanding and the legal level of protection of academic freedom vary widely within European countries. In the US, the principle is often framed as part of freedom of speech and thus protected under the First Amendment (Karran 2009); but, as we could see, this does not in any way insulate it against widely differing interpretations of how it should be applied in practice.

While the Salaita case can be considered foundational in terms of making these questions central to a prolonged public controversy as well as a legal dispute, navigating the terrain in which these controversies arise has progressively become more complicated. Carrigan (2016) and Lupton (2014) note that almost everyone, to some degree, is already a ‘digital scholar’. While most human resources departments as well as graduate programmes increasingly offer workshops or courses on ‘using social media’ or ‘managing your identity online’ the issue is clearly not just one of the right tool or skill. Inevitably, it comes down to the question of boundaries, that is, what ‘counts as’ public engagement in the ‘digital university’, and why? How is academic work seen, evaluated, and recognised? Last, but not least, who decides?

Rather than questions of accountability or definitions of academic freedom, these controversies cannot be seen separately from questions of ontology, that is, questions about what entities are composed of, as well as how they act. This brings us back to assemblages: what counts as being a part of the university – and to what degree – and what does not? Does an academic’s activity on social media count as part of their ‘public’ engagement? Does it count as academic work, and should it be valued – or, alternatively, judged – as such? Do the rights (and protections) of academic freedom extend beyond the walls of the university, and in what cases? Last, but not least, which elements of the university exercise these rights, and which parts can refuse to extend them?

The case of George Ciccariello-Maher, until recently a Professor of English at Drexel University, offers an illustration of how these questions impact practice. On Christmas Day 2016, Ciccariello-Maher tweeted ‘All I want for Christmas is white genocide’, an ironic take on certain forms of right-wing critique of racial equality. Drexel University, which had been closed over Christmas vacation, belatedly caught up with the ire that the tweet had provoked among conservative users of Twitter, and issued a statement saying that ‘While the university recognises the right of its faculty to freely express their thoughts and opinions in public debate, Professor Ciccariello-Maher’s comments are utterly reprehensible, deeply disturbing and do not in any way reflect the values of the university’. After the ironic nature of the concept of ‘white genocide’ was repeatedly pointed out both by Ciccariello-Maher himself and some of his colleagues, the university apologised, but did not withdraw its statement.

In October 2017, the University placed Ciccariello-Maher on administrative leave, after his tweets about white supremacy as the cause of the Las Vegas shooting provoked a similar outcry among right-wing users of Twitter.1 Drexel cited safety concerns as the main reason for the decision – Ciccariello-Maher had been receiving racist abuse, including death threats – but it was obvious that his public profile was becoming too much to handle. Ciccariello-Maher resigned on 31st December 2017. His statement read: ‘After nearly a year of harassment by right-wing, white supremacist media and internet trolls, after threats of violence against me and my family, my situation has become unsustainable’.2 However, it indirectly contained a criticism of the university’s failure to protect him: in an earlier opinion piece published right after the Las Vegas controversy, Cicariello-Maher wrote that ‘[b]y bowing to pressure from racist internet trolls, Drexel has sent the wrong signal: That you can control a university’s curriculum with anonymous threats of violence. Such cowardice notwithstanding, I am prepared to take all necessary legal action to protect my academic freedom, tenure rights and most importantly, the rights of my students to learn in a safe environment where threats don’t hold sway over intellectual debate.’.3 The fact that, three months later, he no longer deemed it safe to continue doing that from within the university suggests that something had changed in the positioning of the university – in this case, Drexel – as a ‘bulwark’ against attacks on academic freedom.

Forms of capital and lines of flight

What do these cases suggest? In a deterritorialised university, the link between academics, their actions, and the institution becomes weaker. In the US, tenure is supposed to codify a stronger version of this link: hence, Nelson’s attempt to justify Salaita’s dismissal as a consequence of the fact that he did not have tenure at the University of Illinois, and thus the institutional protection of academic freedom did not extend to his actions. Yet there is a clear sense of ‘stretching’ nature of universities’ responsibilities or jurisdiction. Before the widespread use of social media, it was easier to distinguish between utterances made in the context of teaching or research, and others, often quite literally, off-campus. This doesn’t mean that there were no controversies: however, the concept of academic freedom could be applied as a ‘rule of thumb’ to discriminate between forms of engagement that counted as ‘academic work’ and those that did not. In a fragmented and pluralised public sphere, and the growing insecurity of academic employment, this concept is clearly no longer sufficient, if it ever was.

Of course, one might claim in this particular case it would suffice to define the boundaries of academic freedom by conclusively limiting it to tenured academics. But that would not answer questions about the form or method of those encounters. Do academics tweet in a personal, or in a professional, capacity? Is it easy to distinguish between the two? While some academics have taken to disclaimers specifying the capacity in which they are engaging (e.g. ‘tweeting in a personal capacity’ or ‘personal views/ do not express the views of the employer’), this only obscures the complex entanglement of individual, institution, and forms of engagement. This means that, in thinking about the relationship between individuals, institutions, and their activities, we have to take account the direction in which capital travels. This brings us back to lines of flight.

The most obvious form of capital in motion here is symbolic. Intellectuals such as Salaita and Ciccariello-Maher in part gain large numbers of followers and visibility on social media because of their institutional position; in turn, universities encourage (and may even require) staff to list their public engagement activities and media appearances on their profile pages, as this increases visibility of the institution. Salaita has been a respected and vocal critic of Israel’s policy and politics in the Middle East for almost a decade before being offered a job at the University of Illinois. Ciccariello-Maher’s Drexel profile page listed his involvement as

… a media commentator for such outlets as The New York Times, Al Jazeera, CNN Español, NPR, the Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times and the Christian Science Monitor, and his opinion pieces have run in the New York Times’ Room for Debate, The Nation, The Philadelphia Inquirer and Fox News Latino.4

One would be forgiven for thinking that, until the unfortunate Tweet, the university supported and even actively promoted Ciccariello-Maher’s public profile.

The ambiguous nature of symbolic capital is illustrated by the case of another controversial public intellectual, Slavoj Žižek. Renowned ‘Elvis of philosophy’ is not readily associated with an institution; however, he in fact has three institutional positions. Žižek is a fellow of the Institute of Philosophy and Social Theory of the University of Ljubljana, teaches at the European Graduate School, and, most recently has been appointed International Director of the Birkbeck Institute of the Humanities. The Institute’s web page describes his appointment:

Although courted by many universities in the US, he resisted offers until the International Directorship of Birkbeck’s Centre came up. Believing that ‘Political issues are too serious to be left only to politicians’, Žižek aims to promote the role of the public intellectual, to be intellectually active and to address the larger public.5

Yet, Žižek quite openly boasts what comes across as a principled anti-institutional stance. Not long ago, a YouTube video in which he dismisses having to read students’ essays as ‘stupid’ attracted quite a degree of opprobrium.6 On the one hand, of course, what Žižek says in the video can be seen as yet another form of attention-seeking, or a testimony to the capacity of new social media to make everything and anything go ‘viral’. Yet, what makes it exceptional is exactly its unexceptionality: Žižek is known for voicing opinions that are bound to prove controversial or at least thread on the boundary of political correctness, and it is not a big secret that most academics do not find the work of essay-reading and marking particularly rewarding. But, unlike Žižek, they are not in a position to say it. Trumpeting disregard for one’s job on social media would, probably, seriously endanger it for most academics. As we could see in examples of Salaita and Ciccariello-Maher, universities were quick to sanction opinions that were far less directly linked to teaching. The fact that Birkbeck was not bothered by this – in fact, it could be argued that this attitude contributed to the appeal of having Žižek, who previously resisted ‘courting’ by universities in the US – serves as a reminder that symbolic capital has to be seen within other possible ‘lines of flight’.

These processes cannot be seen as simply arising from tensions between individual freedom on the one, and institutional regulation on the other side. The tenuous boundaries of the university became more visible in relation to lines of flight that combine persons and different forms of capital: economic, political, and symbolic. The Salaita controversy, for instance, is a good illustration of the ‘entanglement’ of the three. Within the political context – that is, the longer Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and especially the role of the US within it – and within the specific set of economic relationships, that is, the fact US universities are to a great degree reliant on funds from their donors – Salaita’s statement becomes coded as a symbolic liability, rather than an asset. This runs counter to the way his previous statements were coded: so, instead of channelling symbolic capital towards the university, it resulted in the threat of economic capital ‘fleeing’ in the opposite direction, in the sense of donors withholding it from the university. When it came to Ciccariello-Maher, from the standpoint of the university, the individual literally acts as a nodal point of intersection between different ‘lines of flight’: on the one hand, the channelling of symbolic capital generated through his involvement as an influential political commentator towards the institution; on the other, the possible ‘breach’ of the integrity (and physical safety) or staff and students as its constituent parts via threats of physical violence against Ciccariello-Maher.

All of this suggests that deterritorialization can be seen as positive and even actively supported; until, of course, the boundaries of the institution become too porous, in which case the university swiftly reterritorialises. In the case of the University of Illinois, the threat of withdrawn support from donors was sufficient to trigger the reterritorialization process by redrawing the boundaries of the university, symbolically leaving Salaita outside them. In the case of Ciccariello-Maher, it would be possible to claim that agency was distributed in the sense in which it was his decision to leave; yet, a second look suggests that it was also a case of reterritorialization inasmuch as the university refused to guarantee his safety, or that of his students, in the face of threats of white supremacist violence or disruption.

This also serves to illustrate why ‘unbundling’ as a concept is not sufficient to theorise the processes of assembling and disassembling that take place in (or on the same plane as) contemporary university. Public engagement sits on a boundary: it is neither fully inside the university, nor is it ‘outside’ by the virtue of taking place in the environment of traditional or social media. This impossibility to conclusively situate it ‘within’ or ‘without’ is precisely what hints at the arbitrary nature of boundaries. The contours of an assemblage, thus, become visible in such ‘boundary disputes’ as the controversies surrounding Salaita and Ciccariello-Maher or, alternatively, their relative absence in the case of Žižek. While unbundling starts from the assumption that these boundaries are relatively fixed, and it is only components that change (more specifically, are included or excluded), assemblage theory allows us to reframe entities as instantiated through processes of territorialisation and deterritorialization, thus challenging the degree to which specific elements are framed (or, coded) as elements of an assemblage.

Conclusion: towards a new political economy of assemblages

Reframing universities (and, by extension, other organisations) as assemblages, thus, allows us to shift attention to the relational nature of the processes of knowledge production. Contrary to the narratives of university’s ‘decline’, we can rather talk about a more variegated ecology of knowledge and expertise, in which the identity of particular agents (or actors) is not exhausted in their position with(in) or without the university, but rather performed through a process of generating, framing, and converting capitals. This calls for longer and more elaborate study of the contemporary political economy (and ecology) of knowledge production, which would need to take into account multiple other actors and networks – from the more obvious, such as Twitter, to less ‘tangible’ ones that these afford – such as differently imagined audiences for intellectual products.

This also brings attention back to the question of economies of scale. Certainly, not all assemblages exist on the same plane. The university is a product of multiple forces, political and economic, global and local, but they do not necessarily operate on the same scale. For instance, we can talk about the relative importance of geopolitics in a changing financial landscape, but not about the impact of, say, digital technologies on ‘The University’ in absolute terms. Similarly, talking about effects of ‘neoliberalism’ makes sense only insofar as we recognise that ‘neoliberalism’ itself stands for a confluence of different and frequently contradictory forces. Some of these ‘lines of flight’ may operate in ways that run counter to the prior states of the object in question – for instance, by channelling funds, prestige, or ideas away from the institution. The question of (re)territorialisation, thus, inevitably becomes the question of the imaginable as well as actualised boundaries of the object; in other words, when is an object no longer an object? How can we make boundary-work integral to the study of the social world, and of the ways we go about knowing it?

This line of inquiry connects with a broader sociological tradition of the study of boundaries, as the social process of delineation between fields, disciplines, and their objects (e.g. Abbott 2001; Lamont 2009; Lamont and Molnár 2002). But it also brings in another philosophical, or, more precisely, ontological, question: how do we know when a thing is no longer the same thing? This applies not only to universities, but also to other social entities – states, regimes, companies, relationships, political parties, and social movements. The social definition of entities is always community-specific and thus in a sense arbitrary; similarly, how the boundaries of entities are conceived and negotiated has to draw on a socially-defined vocabulary that conceptualises certain forms of (dis-)assembling as potentially destructive to the entity as a whole. From this perspective, understanding how entities come to be drawn together (assembled), how their components gain significance (coding), and how their relations are strengthened or weakened (territorialisation) is a useful tool in thinking about beginnings, endings, and resilience – all of which become increasingly important in the current political and historical moment.

The transformation of processes of knowledge production intensifies all of these dynamics, and the ways in which they play out in universities. While certainly contributing to the unbundling of its different functions, the analysis presented in this article shows that the university remains a potent agent in the social world – though what the university is composed of can certainly differ. In this sense, while the pronouncement of the ‘death’ of universities should be seen as premature, this serves as a potent reminder that understanding change, to a great deal, depends not only on how we conceptualise the mechanisms that drive it, but also on how we view elements that make up the social world. The tendency to posit fixed and durable boundaries of objects – that I have elsewhere referred to as ‘ontological bias’7 – has, therefore, important implications for both scholarship and practice. This article hopes to have made a contribution towards questioning the boundaries of the university as one among these objects.

——————–

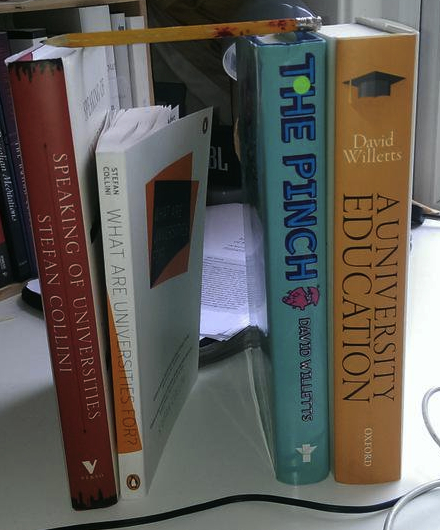

If you’re interested in reading more about these tensions, I also recommend Mark Carrigan’s ‘Social Media for Academics’ (Sage).

Prologue

Prologue

![One more time with [structures of] feeling: anxiety, labour, and social critique in/of the neoliberal academia](https://janabacevic.files.wordpress.com/2016/08/906736_10151382284833302_1277162293_o.jpg?w=924&h=0&crop=1)