My best friend and I used to finish every party at my place sitting by windows that were flung wide open, feet propped up on the ledge, smoking, listening to music, and waiting for the dawn to break. Staying behind to help with the dishes was, back in the day, the ultimate token of friendship: my family did not own a dishwasher (it broke down sometime in the early 1980s and it would not be until mid-2000s that political and financial stability were sufficient to buy a new one); there was always a lot of cleaning up to do after a party. These early-morning moments became our after, where we could watch the day rise, safe in the knowledge both mild ignominies and larger embarrassments of the night before were put to sleep, together with the dishes.

One of the songs we used to listen to in such moments was U2’s ‘Stay (Faraway, So Close!’). I’m not sure whether this was before U2 Sold Out or Became Uncool, or because we were just too cut off from that iteration of the ‘culture wars’, in the country still called Yugoslavia deep in the throes of an actual war, to notice or care. Or maybe we were just a little too enamoured of Wim Wenders’ ‘Das Himmel Uber Berlin’ (‘Wings of Desire’ is its English title, sadly probably one of the worst translations ever) or its eponymous sequel, for which the song was recorded.

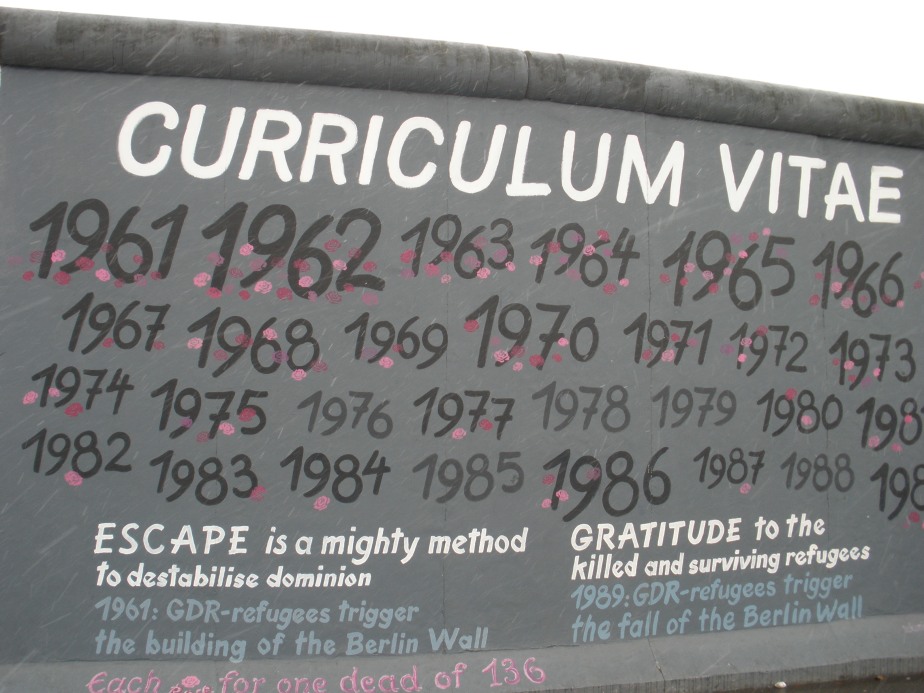

The period between these two films was also the period during which the events that would mark our childhoods unravelled. “Wings of Desire” was shot in 1987, in a Berlin whose dividing line will soon turn to rubble. “Faraway, So Close” premiered in 1993. Longer-brewing political conflict in what was then known as the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia surfaced in 1988/9, and transformed into a full-scale war in 1991.

In 1991, Croatia and Slovenia declared independence. The first anti-Milosevic protests happen in Belgrade. Almost everyone I know is at this protest.

Yugoslav army forces enter Slovenia. Two Serb secessionist entities form in Croatia and in Bosnia. All sides are armed.

In 1992, the siege of Sarajevo begins.

It will take another three years until the Dayton Peace Agreement, and another ten until the war is effectively over. I was eight when I confidently declared to my father that I think Slovenia will secede from Yugoslavia, and twenty when the war ended. I spent most of my childhood and teens alternating between peace & anti-regime protests, and navigating the networks of violence, misogyny, and hate that conflicts like these tend to kick up. In my late twenties and early thirties, part of my career will be dedicated to dealing specifically with post-conflict environments; and so, in the broader sense, was my book.

At any rate, as we sat by the window ledge sometime between the second half of the 1990s and the first half of 2000s, the lyrics of the song precipitated the whole wide world, which was in stark contrast with the fact that sanctions, visa regimes, and plummeting economy made it exceedingly difficult to travel. Those who did mostly did it in one direction.

Faraway, so close

Up with the static and the radio

With satellite television

You can go anywhere

Miami, New Orleans

London, Belfast and Berlin

Sometimes, we would swap ‘Belfast’ for ‘Belgrade’, just for the fun of it, but also to make clear that we considered our city, Belgrade, to be part of the world. The promise of connection, of ‘satellite television’ (watching MTV through one of the local channels). The promise that there is a world out there, and that just because we could not see it did not mean it has disappeared.

In the intervening years, I would go to London, Belfast, and Berlin (I’ve still not been to Miami or New Orleans). I would live in London – briefly – and also, more permanently, in Oxford, Budapest, Bristol, Copenhagen, Auckland, Cambridge, Durham, and Newcastle. My friend, though she will travel a bit, will remain in Belgrade.

***

It is 3 May 2023 in Belgrade, 8AM Central European Time (CET). CET is one hour ahead of British Summer Time (BST), which is the time zone in the northeast of England, where I normally live. It is also six hours ahead of EDT (Eastern Daylight Time), which is where I am, in upstate New York. I am here on my research leave – that’s sabbatical in British English – from Durham University, at Bard College. It is 2AM, and I am sound asleep.

At this time, in the entrance of an elementary (primary+lower secondary) school in Belgrade, a 13-year-old opens fire from a semi-automatic rifle, hitting and killing a security guard, injuring two students, before moving down the corridor on the right to the classroom on the left, where he opens fire again, injuring a teacher and killing another eight students. The classroom is my classroom – ‘homeroom’ between 1992 and 1996. The school is the elementary school both me and my best friend attended from 1988 to 1996.

It is 7AM EDT in Red Hook; 1 PM CET. I wake up, going through the usual routine of stretching-coffee-breakfast. I go for a run. I do not check social media, because I need to focus on the talk I am giving that afternoon. The talk is part of my fellowship at the Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and Humanities at Bard. It is on spaces and places of thought and violence.

It is 12PM EDT, and 6PM CET. I’m having lunch with Anthony, who’s a friend and also the editor of The Philosopher, the journal whose board I’m on, and another member of the editorial board.

It is 4PM EDT, and 10PM CET. I’m giving the talk. It’s entitled ‘How to think together’, and it’s a product of anything from two months to twenty years of thinking about how to coexist with others, including across political difference. [you can watch the recording here].

It is 10PM in Red Hook. I have just come back from the post-talk dinner, buzzing from pleasant conversation and the wine. I log on to social media – I see nothing on Twitter, and then, for some reason, I log on to Facebook, which I rarely use (mostly for friends and family in Serbia).

It is 4AM on 4 May in Belgrade. Flowers have been amassed; the candles lit; the vigils held. My friends have hugged and held each other. All of them (quick check on Facebook) are safe, also their children who go to the same school. All of them are safe: none of them are OK.

And, for that matter, neither am I.

***

What is the purpose, the value of mourning at a distance? As the week unfolds, I turn this question over and over again in my head, my ethical, normative, political and affective registers crashing and collapsing against each other.

“I have no right to mourn, I wasn’t even there” to “I wish I could have been there, and I wish I could have taken at least one of those bullets”.

“These kinds of things happen in the USA all the time, why am I suddenly so impacted by this?”

From “Fantasies of self-sacrificing heroism are a wish for immortality/covert fear of death, cut it out” to “There is nothing I can do nor any use I can be of from here, feeling this way is self-indulgent”.

From “I want to go home” to “Home is the north of England, what difference would being there make?”

What right do I have to mourn from a distance?

What does distance do to a feeling?

***

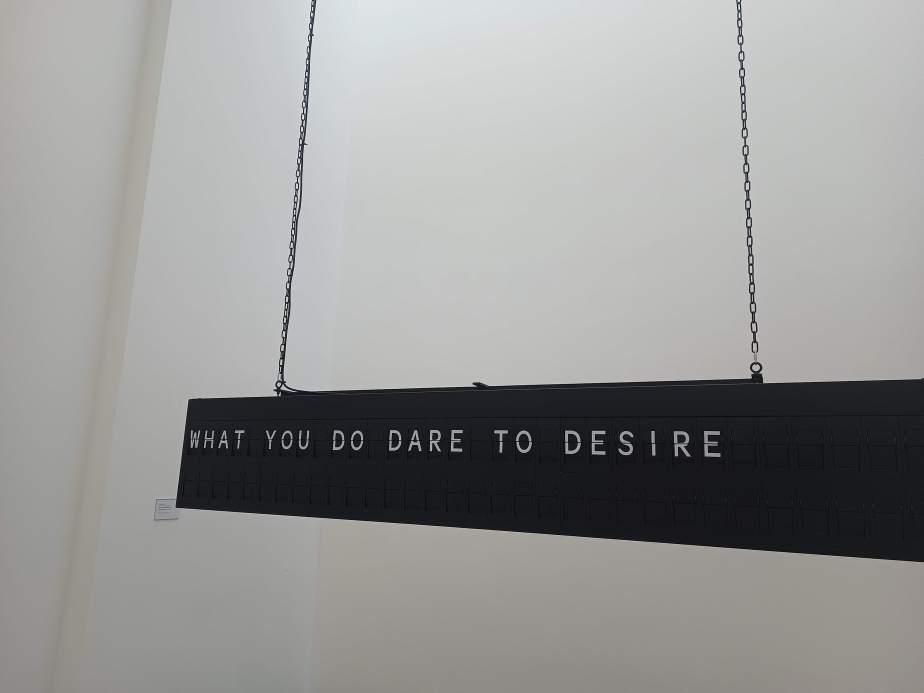

Distance, proximity, detachment and engagement have been among the key themes of my thinking, writing, and, inevitably, life (this blog, for instance, was born out of exploring these themes in both theory and practice). Away is both a mode of escape or distance, and of sustaining desire: being seen but not held (too tight), acknowledged but never (fully) known, alone but never isolated. Or at least that was the ideal. As years went on, it became less and less a moral, ethical or aesthetic choice, and more a simple fact of life. Academic mobility combined with endless curiosity meant I accepted – and, to be honest, welcomed – the constant movement. I regretted that relationships broke apart because of this; I reluctantly accepted that my dislike of heteropatriarchal, monogamous, nuclear family patterns as fundamental social units meant I was likely to struggle to form new ones, especially as more and more friends were having children. A fact of life then became an adaptation strategy: to accept the impermanence of all things; to always have one foot out of the door. Ready to detach and withdraw, there for people should they need me, but not to burden them with my presence, or needs. Or feelings.

Congruent with my other beliefs, being away quietly stopped being a location, and became an answer.

This mode of inhabiting the world resembles what Peter Sloterdijk in The Art of Philosophy frames as being “dead on holiday”, the practice of studied detachment that first came to define the social role of professional thinkers. This position entails the denial not only of bodily functions and of mortality, but also of time itself; to take up semi-permanent residence in the realm of pure forms means exiting human time as it known. The theme of exiting human space/time is, of course, common to all ‘otherworldly’ practices and belief systems – from Greek philosophy to Christianity to mysticism and whatever happened in between (or: outside, as after all, we do not have to conform to human time). This, of course, is also what both Wenders’ films are about; distance, and desire, and time.

Hannah Arendt, who engaged with this dichotomy and its implications before Sloterdijk, notes that this position – as conducive to thinking as it is – also means we remain isolated from others:

Outstanding among the existential modes of truth-telling are the solitude of the philosopher, the isolation of the scientist and the artist, the impartiality of the historian and the judge (…) These modes of being alone differ in many respects, but they have in common that as long as any one of them lasts, no political commitment, no adherence to a cause, is possible. (…) From this perspective, we remain unaware of the actual content of political life – of the joy and the gratification that arise out of being in company with our peers, out of acting together and appearing in public.

(Arendt, ‘On Politics’, 2005: 62).

Arendt argues that this is what makes the realm of thought – ‘pure speculation’ – separated from politics. Theorizing rests on the ability to distance oneself not only from the immediacy of reality (something Boltanski explores in On Critique), but also on the ability to suspend judgment; that is, to retain a sufficient degree of distance/detachment from the object (of contemplation) so as to be able to comprehend them in their entirety.

The PhD I wrote in 2019 explored this complex operation insofar as it is involved in the production of critical social theory, in particular the critique of neoliberalism as concept [a concise version, in article form, is here; I drew on Boltanski, Chiapello, Arendt, and Sloterdijk but also went beyond them]. I called it ‘gnossification’ for the tendency to turn complex, ambiguous, and affectively-loaded phenomena into objects of knowledge. This isn’t simply to ‘rationalize’ or ‘explain away’ one’s feelings: we can be blindest about our own feelings when we confront them, as it were, head-on. The point is that gnossification also performs the affective work of creating and maintaining that distance, for the mere fact that it locates our field of vision in our own interiority. It literally produces (affective, perceptive, cognitive) space. And because space is relational (or, as Einstein would have put it, relative), it both requires other objects and cannot but treat them as such.

(If you’d like to hear more about this, I’m always happy to expand 😊).

But doing theory or philosophy is not the only way one can take up semi-permanent residence in the realm of the dead. We can do it through relationship choices (or avoidance of choices). In On Not Knowing, Emily Ogden encapsulates this beautifully and succinctly:

It is not only in death itself that we encounter the temptation to prescind from life. What it means for death to claim us is that the sterile round of our routines claims us. We no longer see the point or the possibility of a pleasant surprise…Death claims us in the passion some of us have for disposing of our lives, equally in the taking of excessive risks and the settling of marriages. And those two things are not even incompatible: it is possible to ‘sow one’s wild oats’ in the name of settling down. Put me, I beg you, in a rut.

Ogden draws extensively on the work of psychoanalyst and philosopher Anne Dufourmantelle. In In Praise of Risk, Dufourmantelle characterizes this kind of strategy as concerned with avoiding the inevitable ambiguity of existence:

the risk of ‘not yet dying’, this gamble that we will always lose in the end, but only after traversing life with more or less plenitude, joy, and most of all, intensity.

Or, of course, pain.

***

To mourn from a distance: to recognize that no amount of distance – linguistic, conceptual, geographical, emotional – can protect us from the pain of others.

To love at a distance: to know that feeling has no natural connection to proximity, and that this is not the answer but the beginning of a question or, more likely, the question: how to care for others – and to let them care for us – even if we have chosen not to be physically close to them.

To feel at a distance: to understand that it is possible to want to feel the pain, joy, and fear of others, not as a spectator, seer, or helper/healer, but because this is what love – and friendship – is.

***

Friendship, Derrida writes, is a contract with time. In friendship, we make a pact of lasting beyond death. We know our friends will remember us even after we die. And, reciprocally, we accept not only the cognitive but also the emotional task of keeping their memory alive: in simpler terms, we accept we will both remember and miss them.

To love is to accept that there are objects whose presence is felt regardless whether we have chosen them as objects of contemplation. It is to receive the reminder that things can’t be ‘switched off’, even for those of us with significant training, capacity, and experience in doing so. To love means to, essentially, live with others even if we choose not to live together. For someone whose probably most successful and effectively longest relationship was predominantly long-distance, but who was also taught to associate this tendency with narcissism and avoidance of intimacy, this is a difficult lesson.

Back in the early oughts, on a website called everything2 (think like anarchist – no, chaotic – Wikipedia, but with stories, poetry and fiction interspersed with information), there was a post written from the perspective of someone who is spending the winter in one of the research stations in the Antarctica (yes, this was a job I’d considered, and were it not for the unfortunate fact of Serbian passport, would have still very much liked to do). I can’t reproduce much of the post – I didn’t save it, and repeat attempts over the years have failed to resurface it – but I remember the line on which it ends: “I still see you, and I love you very, very much”. The point being that distance, at the end of the day (or the end of the world?), makes very little difference at all.

Being dead on holiday officially over, I begin to pack to go back to the UK, and thus also to leave – even if temporarily – the US, which now holds most of these realizations for me. Not screaming ‘Behold, I am Lazarus’, because this is not a miracle, not even a tiny one. It is more of a coincidence, a set of circumstances, though thanks will be given where thanks are due, because I owe this to so, so many people. You know who you are, and I love you.