Dreams are dangerous places. The control and awareness we tend to ascribe to what is usually referred to as ‘dreams’ in the waking state (ambitions; aspirations) is the exact opposite of the absence of control we tend to assume of dreams in the unconscious (sleeping) state, but neither is, strictly speaking, true; we do not choose our ambitions or orientations with full awareness, much like it is ridiculous to fully outsource authoriality when we sleep.

Psychoanalysis, of course, knows this. But, much like other disciplines and traditions that take dreams seriously, it is all-too-often equated with treating dreams as epistemology; that is, using dream logic to deduce something about the person who dreams, as if exiting from the forces generating the unconscious (in Freud’s formulation, following Ariadne’s thread) is ever truly possible. Sociology, needless to say, hardly does a better job, instead placing dreams at the uncomfortable (all boundaries, for sociology, are uncomfortable) boundary between collective and individual, as if the collective (unconscious) somehow permeates the individual, but always imperfectly (everything, in sociology, is imperfect, except its own imperfections).

Bion describes pathology as the inability to dream and inability to wake up; but is this not another (even if relaxed) call for discreteness, ushering in Freud’s Reality principle through the back door? This seems relevant given the relevance of the ability to dream (and dream differently) for any progressive movement or politics. What if elements of reality become so impoverished that there is nothing to dream about? This is one of the things I remember most clearly from reading Cormac McCarthy’s’s The Road – good, happy, and peaceful dreams usually mean you are dying. Reality, in other words, has become so unbearable that there is nothing but retreat into personal, individualized fantasy as a bulwark against this (this is also, though in a more complicated tone, a motif in one of my favourite films, Wenders’ Until the End of the World).

There are several possible ways out of this. One is to see dreams as shared; that is, to conceptualize dreaming as a collective, rather than solitary activity, and dreams as a possession of more than a single individual. Yet, I fear this too-easily slips into platitudes; as much as dreams (and beliefs, and feelings, and thoughts) can be similar and communicated, it is unlikely they can literally be co-created: individual mental states remain (and, in some cases, are indistinguishable from) individual.

(I’m aware that the Australian Aboriginal concept of Dreamtime may challenge this, but I’m reserving that for a different argument).

Instead of imagining some originary dream-state in which we are connected through other minds as if via a umbilical cord, I’m increasingly thinking it makes sense to conceptualize dreams as places; that is, instances of timespace with laws, sequences, and sets of actions and relations. In this sense, we can be in others’ dream(s), as much as they can be in our(s); but within this place, we are probably still responsible to ourselves. Or are we?

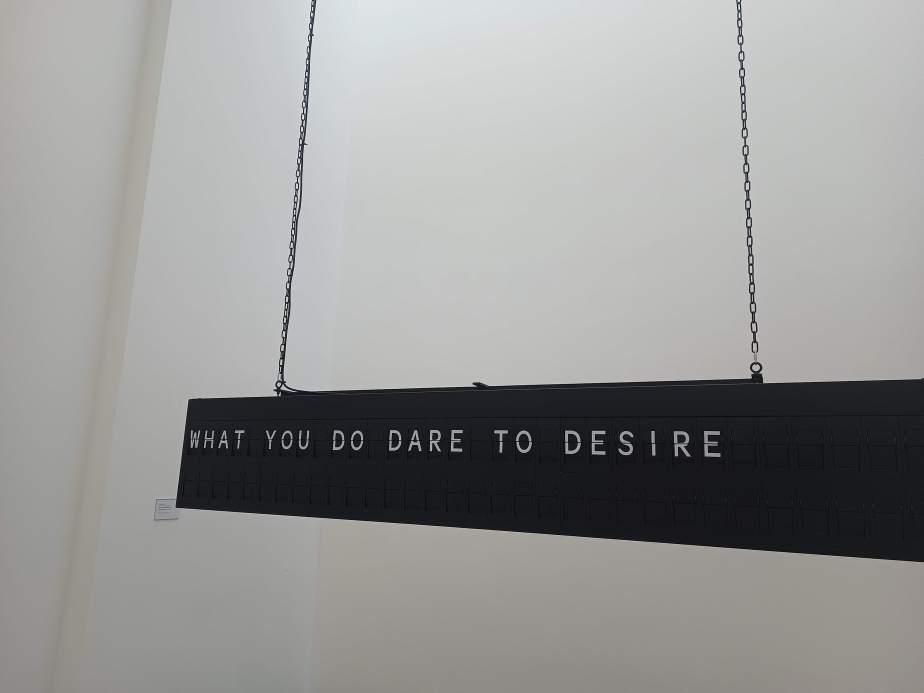

How free are you to act in someone else’s dream?